tBrief #08 – Does size matter? The challenge of fisheries transparency in Small Island Developing States (SIDS)

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are prominent custodians of our blue planet, owning vast areas of the ocean. This includes most of the world’s tropical coral reefs and some of the most productive fishing grounds. Transparency has therefore an elevated importance for fisheries management in these SIDS.

But while SIDS receive increasing global attention – unfortunately, mostly due to their vulnerabilities – there is no internationally agreed definition of what constitutes a small island developing state. Consequently, the list of countries classified as SIDS varies depending on its source: The number of sovereign states recognised as SIDS by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is smaller (32) than those recognised by the United Nations (37) or the Alliance of Small Island States (39).

Furthermore, the label of SIDS covers a wide range of countries with diverse characteristics, including countries that are not small in terms of their populations (e.g. Papua New Guinea with nearly 9 million people), are not islands (i.e. Belize, Suriname, Guyana and Guinea Bissau) or are not developing states, with several that meet the World Bank criteria as having high per capita incomes (i.e. Singapore, Seychelles, Barbados).

What is remarkable is that SIDS are home to less than 1% of the world’s population, but they account for over 30% of the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of the ocean, including parts with some of the highest biodiversity of our blue planet. It is therefore obvious that SIDS include states that are among the most ‘fish dependent’ societies in the world. For example, in the Pacific fish consumption is estimated to be four times higher than the global average. And while transparency and public participation is starting to be prioritised by SIDS for their fisheries sector (including through several fisheries initiatives in the Caribbean, the Pacific and Africa), progress remains patchy.

- One such aspect relates to the licensing of industrial fishing and the use of the resulting revenues. Many SIDS are still failing to make this information public.

- There is also a worrying lack of transparency surrounding the international trade in sea cucumbers: a booming industry for many SIDS, generating an estimated US$50 million annually in the Pacific alone.

- Additionally, as we have documented in our TAKING STOCK transparency assessments for Comoros, Mauritius and São Tomé and Príncipe, many SIDS fail to produce social and environmental information on coastal fisheries and the post-harvest sector, which is critical for informed national policy debates, particularly as many SIDS are taking strides to develop their blue economies.

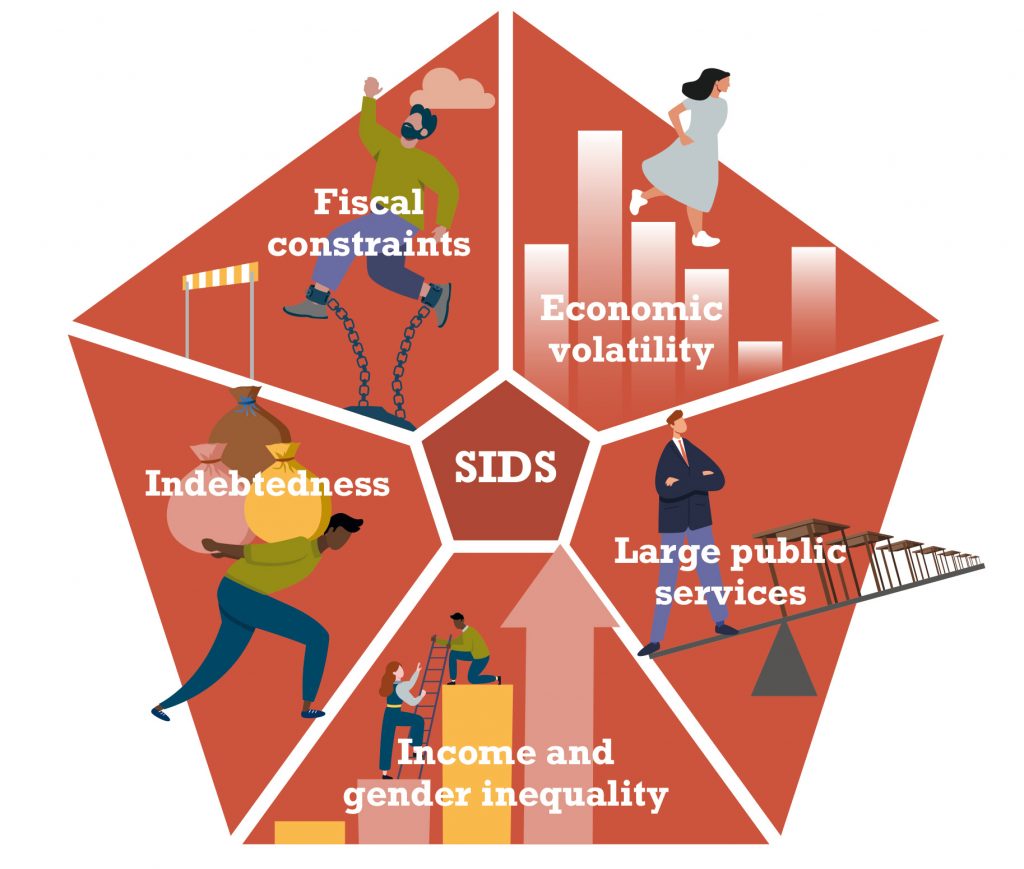

In this latest edition of our tBrief series, we explore the importance of fisheries transparency for SIDS, as well as its barriers and opportunities for progress. As a starting point, the tBrief summarises the several distinctive social and economic features of SIDS, which form an essential background for exploring fisheries governance.

In many respects, the challenges that SIDS face in achieving and maintaining strong public access to information are the same found in many other coastal states. However, there are two additional themes which stand out:

The challenge of data deficiency: Many SIDS face considerable practical barriers to collating certain types of information that are the focus of transparency reforms, such as the FiTI. For example, surveys of fishers and assessments of fish stocks are challenging for governments of SIDS, particularly those that have numerous smaller islands. Vanuatu is perhaps the most extreme example: it has a population of 300,000 people, but they are spread out over 65 different islands, with as many as 100 distinct local dialects. SIDS tend to experience more costly service provision due to their remoteness and geographical expanse. When we add to this the economic shocks caused by climate disasters, we should appreciate that fisheries authorities struggle to maintain consistent and comprehensive data.

The challenge to achieve ʻinstitutions of accountability’: There are several reasons why the demand for transparency might not be as strong in SIDS as it is in other coastal states. This is partly due to the dynamics of countries with very small populations, having a high degree of personal familiarity between citizens and government officials. One of the contentious attributes of SIDS is their tendency towards clientelism, which could pose a barrier to creating a more open and accountable government. The media in SIDS is also described in many studies as being weak and lacking political independence. Yet transparency initiatives thrive where there is a public audience willing and able to scrutinise government data and speak openly about government failures.

As we argue in this tBrief, none of these barriers to transparency and public participation in fisheries are unsurmountable. There are also positive dimensions to appreciate. While small hyper-personalised societies might be resistant to transparency, they may also be dynamic communities that embrace new forms of deliberative democracy. Furthermore, there is growing demand within SIDS for democratic reforms, particularly concerning the inclusion of women in decision-making processes. In doing so it seems vital to avoid the trap of equating transparency with only fighting crime and corruption. The benefits of an open and inclusive government are far more than this, and that has to be at the forefront of transparency efforts for SIDS, or ‘Big Ocean States’ (BOSS).

We hope that you enjoy reading this tBrief. If you have any comments, questions or suggestions, please contact us.

You can download the tBrief in the following four languages:

This publication is funded by Irish Aid. Other tBrief editions can be found here.